/The annual cycle: a strategy for invasion

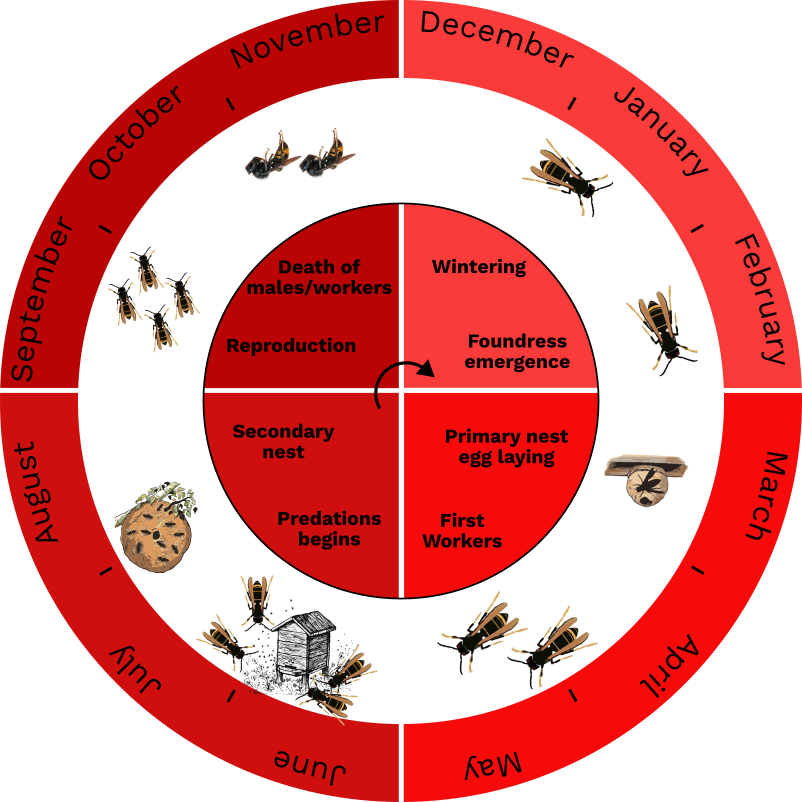

The success of the yellow-legged hornet lies in its highly adapted annual lifecycle. Unlike species that survive with multiple queens, the Asian hornet colony is seasonal, founded by a single, fertilized queen. Understanding this cycle is key to timing effective control measures.

Spring: The founding queen emerges

The cycle begins in spring, typically from February to April, when temperatures consistently rise above 10-13°C (source 1). A single, mated queen (a “foundress”) emerges from hibernation. She is the sole survivor of the previous year’s colony. Her first task is to find a source of sugar for energy (tree sap, nectar) and then to seek a protected location to build a primary nest.

- Behavior: The queen works alone, constructing a small, papery nest and laying the first eggs.

Summer: The colony expands

The first eggs hatch into sterile female workers. Once the first generation of workers emerges (around May/June), the queen remains in the nest, dedicated solely to egg-laying. The workers take over all other duties: expanding the nest, foraging for food (insects, meat, fruit), and caring for the larvae.

- Rapid growth: The colony population grows exponentially throughout the summer. The primary nest may become too small, leading the colony to often construct a much larger secondary nest in a more exposed, elevated location, like a tree canopy (source 2).

- Foraging focus: Worker activity is highest. Pressure on apiaries intensifies as the demand for protein (to feed larvae) increases.

Autumn: The final generation

In late summer and early autumn (from August onwards), the colony’s focus shifts. The queen begins to lay eggs that will develop into new queens (gynes) and males (drones), instead of workers.

- Reproductive phase: These new sexuals leave the nest to mate. After mating, the males die.

- Colony decline: The founding queen dies, and the worker population begins to decline. The colony’s organization breaks down, and foraging becomes less coordinated.

Winter: Hibernation and survival

Only the newly mated queens survive the winter. They seek sheltered spots to hibernate individually—under tree bark, in rock crevices, or even in human-made structures like attics or sheds (source 3). The rest of the colony, including the old queen, all workers, and males, dies off. The empty nest is not reused.